Le Nouvelle Vague

November 8, 2007

So there’s these bratty French kids that grow up to be bratty French young adults, but they love Le Cinema, they watch everything they can, and they particularly like all this low budget neo-realism stuff coming from Italy. They also admire certain American directors like Orson Welles and John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock. Somehow this group of bratty abandoned youth all get jobs writing for this new magazine called Les Cahiers du Cinema (“the cinema papers”). They used their status as writers and critics to complain about all the garbage that French filmmakers were churning out. One in particular, Francois Truffaut, wrote an essay called “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema” where he complained about Le Cinema du Papa (“the father’s cinema”) and how all the movies were overblown historical epics with no real personality or vision, just calculated to make a lot of money. He wanted to see more personal films like those of Welles, Hitchcock, De Sica, Bergman, and Fellini, who he considered to be “Auteurs”.

According to Truffaut’s auteur (that’s french for “author”) theory, certain directors are the authors, the main creative force behind their work. Auteurs have a personal vision, often write their own scripts, have creative control over the whole project, and have a unique style. Hired directors, on the other hand, have a conformed vision, are hired after the script is already written, only partial control over the project (the producer can dictate changes), and have a generic style. Granted, there are some problems with this theory. What about Tim Burton. Unique style, sure, but doesn’t write his own scripts, and while he was fresh and inventive in his earlier years, has tended to keep doing the same thing over and over. Or what about Stephen Soderberg? He doesn’t necessarily have a set “style.” Every film of his is different, not all are great, but he’s always trying new things and taking chances.

Anyway, in 1959, Truffaut and a few of his writer friends took matters into their own hands and started making films themselves. This started what is now known as Le Nouvelle Vague, or the French New Wave.

First, you’ll want to check out this little documentary made by some french student. Not the best edited thing, but pretty informative.

Neo-Realism

November 5, 2007

Download the worksheet here: Neorealism handout

Way back during the first week of class we talked about the three main types of filmmaking: Realism, Classicism, and Formalism. Now, thinking of everything we’ve seen since then, where would you classify them? Pretty much everything was along the lines of classicism, with the occaisional foray into formalism. Maybe The Grapes of Wrath is on the realism side, but that was the rare exception for Hollywood.

But after World War II things started to change. Before the war, Italy was one of the most prolific and influential filmmaking countries. They specialized in huge budget epic films, with giant sets and thousands of actors. But during the war, Italy was occupied by the Germans, then the Americans, and was pretty much torn up by all the fighting. After the war, there weren’t any usable studios, the big name actors had all left, and there was very little money for film equipment. So the filmmakers took to the streets and made simple stories about the struggles of everyday people. This movement later on became known as Neo-realism.

Here’s two chapters from Martin Scorsese’s documentary about Italian Cinema called “My Voyage to Italy.”

As you can see, these early Italian films had a huge impact on Scorsese, both as a person and a filmmaker. When Roberto Rosselini’s film Rome, Open City came out in 1945, it opened the eyes of a lot of potential filmmakers. They realized that to make a film you didn’t need a huge budget and special effects and big name actors. You could make stories about your own life experiences with very little money.

Here’s a few more examples:

Some characteristics of Neo-realism:

- Set in the Present (or near-past). This means that in Italy in 1945-49 there were a lot of films that took place during or right after WWII.

- Non-professional actors. They used regular people that hadn’t acted in film before.

- Shot on already existing locations. No studios or sets.

- Stories about everyday situations and people, the kinds of things most people at the time could relate to.

- Often bleak, somewhat pessimistic, dealing with hardship and poverty.

- Open endings. Not a tragedy where everyone dies. Not a “happy ending” where they achieve their goals. But a frustating ending where we don’t know what’s going to happen.

Film Noir

October 23, 2007

Crime. Fog. Trench coats. Dames. Corruption. Placement advertising for cigarettes. Overhead lights and deep shadows. And overall murderyness. These are some of the things usually associated with the style known as Film Noir. First, you should know that “noir” is French for “noir” which also means black. So when placed after the word “film”, you know you’re dealing with the dark side of society. Film Noir is the flip side of the all-American success story. It’s about people who realize that following the program will never get them what they crave. So they cross the line, commit a crime and reap the consequences. Or, they’re tales about seemingly innocent people tortured by paranoia and butt-kicked by Fate. Either way, they depict a world that’s merciless and unforgiving.

For many movie-lovers, noir is all about style: kanted camera angles, dense shadows, a romantic, doom-laden atmosphere, always in shimmering, high-contrast black and white. In truth, that’s what most people think of as NOIR – rain-slick streets, guys in fedoras, dames in slinky gowns slipping into glistening Packards. It’s a great look, and we’ll never see it again.

These kinds of films became popular after WWII. Folks had seen all the terrible things that people were capable of during the war, and had plenty of doubts as to the meaning of life and the state of humanity. And Hollywood (always looking out for the public good) was more than happy to capitalize on those doubts and fears.

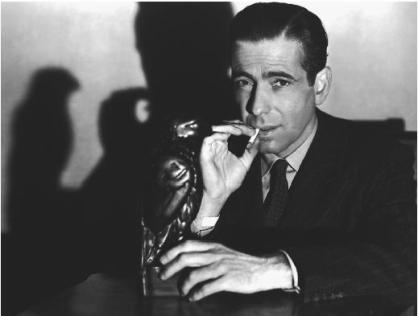

One of the first films noir was John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, starring the inimitable Humphrey Bogart. Here he is:

Pretty cool, huh? Less well known these days, but just as powerful a presence was Robert Mitchum. Take a load of this guy:

That’s right, he’s got “love” and “hate” tatooed on his knuckles.

Click below to watch some clips:

Also check out this cool article on Film Noir

For our feature films we watched The Killing by Stanley Kubrick and Le Samourai by Jean-Pierre Melville.

The Truth about World War II

October 18, 2007

To conclude our survey of documentaries, we studied a bunch of films made during or about World War II. First was Triumph of the Will by Leni Riefenstahl. She had made a few fiction films in Germany and impressed an up and coming political figure named Adolf Hitler, so he hired her to make a documentary about the Nazi party’s convention in 1933. By this time Hitler had been elected chancellor and things were looking up for the German people. He was quite the public speaker and seemed to be leading them up out of poverty, building the labour force and boosting the economy. Little did they know.

Next we saw what Walt Disney was doing at the time to promote the war in America. He made an animated documentary called Victory by Air to convince the government to build up the air force.

Finally we saw one of the most difficult films ever made. Night and Fog, made by Alain Resnais in 1955 is composed of footage they found in germany shot by the nazi soldiers inside the concentration camps, combined with color footage of the ruins of the camps shot by Resnais in ’55. The narration was written by Jean Cayrol who was imprisoned in a concentration camp. The footage of what went on inside the camps is horrifying and infuriating, but stands as a testimony and reminder of what can happen when a majority of a country’s citizens can’t be bothered to stand up for what’s right. Even though by the 40’s most germans didn’t agree with what Hitler was doing, very few had the courage to say “No, I won’t be a part of this.” Instead, as we see in the film, everyone gives the same answer: “I’m not responsible.” “I’m not responsible.” “I’m not responsible.”

It’s All True!

October 12, 2007

What comes to mind when you hear the word “Documentary?” History Channel? Nature? Some British guy holding a microphone telling about science stuff? Let’s face it, the one word most americans (and students at this school) think of when it comes to documentary is “boring.”

They’ve gotten a bad rap over the years, and yes a lot of them can be boring, especially if you’re including the instructional video you have to watch at your first training meeting at McDonalds, or the videorecording of the Math class on channel 9. But there’s also some pretty fantastic, engaging, mind-blowing stuff out there. If you really think that all documentaries are boring, then something is wrong. With you. Or you just haven’t seen any of the good ones.

So these past few days I’ve been doing my utmost to convert new disciples to the beauty of non-fiction filmmaking and watching.

If you haven’t done so already, here’s the worksheet for downloading: documentaries handout The answers are as follows:

What is a documentary? The easy answer is a film concerned with facts and truth and actuality. It contains all sorts of stuff that you probably watch all the time. The ten o’clock news. The home movies of you blowing out the candle on your first birthday cake. Your cousin’s wedding video. The food network. America’s Most Humiliating Home Vidoes. Any sports broadcast. Any of those “reality” shows. That commercial of Alan Thicke telling us about the great deal where you can get a free 3 night stay at that resort in Orlando. Non-fiction film is a huge part of our media consumption. A lot of it is forgetable, but there are some real gems out there. According to scholar Erik Barnouw, one “crucial aspect of the documentary film is its ability to open our eyes to worlds available to us but, for one reason or another, not percieved.”

For example, check out this clip from Microcosmos. This film, by the director of March of the Penguins, is all about the daily life of insects. But rather than the typical nature documentary with some british guy telling us all about the lives and loves and deepest goals of each of the animals, this one has has only one paragraph of narration, which states “But to observe this world, we must fall silent now and listen to its murmurs.” And then there’s no more narration, just really cool footage of insects doing stuff.

Documentaries have a huge range of purposes. Some are informational or educational, the kind you’d watch in your science or history class, or on the discovery network. Some are instructional that actually teach you how to do something, like “this old house” or cooking shows or an excercise video. Some promote awareness of social issues like “Happy Valley” a doc about meth addiction in Utah. Some are tribute to a person or institution, like what they show at the Oscars when Ingmar Berman wins an honorary award, or a video to show at someone’s 50th anniversary or funeral. Some try to convince us of a particular argument, like “Super Size Me” about how bad fast food is for you. Some try to promote change, like Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth.” Some are to preserve memories, like home movies or a concert video. And some are just entertaining and interesting, like “Riding Giants” about big wave surfing.

There are also three main styles of documentary making. The most common is the “omniscient documentary.” This is when you have an unseen, yet all-knowing narrator (often with a low voice and a british accent) who tells us the way things are and we are inclined to believe him (sometimes its a “her”, but rarely). There are interviews with scholars or others in authority. These interviews are professionally done, with nice lighting and cameras on a tripod and everything in its ideal setting. The person asking the questions is edited out to sound like people are just talking on their own. There are often “reinactments” of historical events, with people dressed up in costumes.

Later came a movement known as “direct cinema” or “observational documentary.” This style has no narrator and no interviews. It’s just someone holding a camera filming things that happen as they happen. A good example would be a live concert video. Or that clip from “Microcosmos.” These filmmakers believed that it was most truthful to be as unobtrusive as possible and just catch things on tape as they happen.

Followers of the “Cinema Verite” movement thought the direct cinema stuff was a bunch of crap. If you show up with a camera, people are going to act differently anyway. Plus, depending on your subject, sometimes the filmmaker needs to make things happen. Cinema Verite tends to be confrontational or at least interactive. The filmmaker is often part of the film. She’s on camera talking to people.

Here’s some clips from some docs. You decide what their goal is, and what style of filmmaking they fit into (they might be a combination!)

Meeting People is Easy (a film about Radiohead)

Here’s the worksheet again for download: documentaries handout

The Best Film of All Time?

October 8, 2007

Even though most of the students at EHHS haven’t actually seen Citizen Kane (yet), I’m sure all of them have heard of it and its monolithic reputation as one of the best movies ever. Why is that? Why so highly regarded, so reverently spoken of, so ubiquitously mentioned in lists of top ten whatevers? Well, we here in Film History class are in the process of finding out.

Even though most of the students at EHHS haven’t actually seen Citizen Kane (yet), I’m sure all of them have heard of it and its monolithic reputation as one of the best movies ever. Why is that? Why so highly regarded, so reverently spoken of, so ubiquitously mentioned in lists of top ten whatevers? Well, we here in Film History class are in the process of finding out.

I know when I first saw this film, I thought, “What’s the big deal about that? It was kinda boring. Not like The Shining. Now that’s a great movie.” But actually, when you think about it, there are more than a few similarities to The Shining and Citizen Kane. Both have a huge emphasis on setting and tone. Both show the process of a man destroying himself and everything that’s important to him. Both show someone getting killed by an axe in the chest. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that if it weren’t for Orson Welles and Citizen Kane, Stanley Kubrick would have instead never even gotten interested in film. Instead he would’ve studied chemical engineering, and then gone into teaching, inspiring hundreds of teenagers to dive into the mysteries and beauties of science. He would’ve used his talents for good instead of evil. But thanks to Orson Welles, a young Kubrick bought his first movie camera, pulled off his first dolly shot, and went on to inspire countless youths to ride their bigwheels inside the house, to hit their siblings with a giant bone, to wear their underwear on the outside and assault their elders… Why? Why, Mr. Kubrick, why? I wish you were still alive so I could come visit you in England and punch you in the throat.

Wait… sorry… back to Citizen Kane.

Here’s some things to think about while writing your response:

1. So is it just coincidence that we watched this right after The Grapes of Wrath? (No, it’s not. I planned it that way. But it’s up to you to figure out why.)

2. We know Welles was a huge admirer of John Ford. We also know that he used the same cinematographer, Gregg Toland (who he admired so much, he put Tolan’s name on the same title card as his own, sharing the spotlight as it were). How does the cinematography compare in both films? How was it used symbolically?

3. I know those of you in Mr. Thomas’ english class have been talking up this whole American Dream thing. What does Citizen Kane have to say about that? How does it compare to Grapes of Wrath? Or your own version of that dream?

4. What’s the big deal about this film? Why such a high reputation?

5. What’s up with rosebud?

plenty of things here to keep your minds and pens busy for a page or two.

Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. John Ford

October 2, 2007

When asked by and interviewer in 1967 which directors he most admired, Orson Welles (director of Citizen Kane) answered that he liked “the old masters. By which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. With Ford at his best, you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in the real world.” Previously he had said, “John Ford was my teacher. My own style has nothing to do with his, but Stagecoach was my movie textbook. I watched it over forty times.”

Who is this John Ford? Turns out most of you (with the exception of Kody and Patrick) had no idea. Even though he made over 50 films, and won 4 Academy Awards, not many people tend to see his films these days. Well, kids, thats a shame, and it’s my duty to put a stop to this nonsense.

If you haven’t received one already, you can download the handout here: John Ford Handout

John Ford was known mostly as a director of westerns. Some of his masterpieces include Stagecoach, My Darlin’ Clementine, The Searchers, and The Man who Shot Liberty Valance. But he also did quite a few “prestige” pictures, based on famous literature or historical happenings such as How Green Was My Valley, They Were Expendable, and The Grapes of Wrath. A lot of these might seem a little Old Fashioned now, maybe at times even a little hokey (largely due to the choice of music, which was a problem for the majority of films in the pre-60’s), but at the time he was comparable to someone like Clint Eastwood or Martin Scorsese. In the 1940’s and 50’s if you wanted to see a sweet action film with morally complex characters and beautifully crafted imagery, you waited til the next John Ford film came out. And once you get used to it, there are few directors as satisfying to the soul.

After watching a few clips from previously mentioned films, we watched The Grapes of Wrath in its entirety, and wrote a response to it.

Student Presentations

October 2, 2007

This last week we were treated to a variety of presentations by you, the students. Depending on which class you’re in, you might have learned about The Coen Brothers, Akira Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, Richard Lester, Orson Welles, P.T. Anderson, Serfio Leone (with accompanying soundtrack), Ingmar Bergman, Robert Altman, Chuck Jones, Clint Eastwood, George Melies, Peter Jackson, Werner Herzog, Alfred Hitchcock (who acts in his own trailers), Don Hertzfeld (primitivist animator with his gratuitous use of red ink), James Cameron (directorial debut: The Terminator), and some dude that makes weirdo (I mean, uh, totally rad…) Russian Vampire movies.

We did not, however, have any presentations on Andrei Tarkovsky or Hayao Miyazaki, or George A. Romero, or Jim Jarmusch, among others. You know who you are. And how dissapointed I am. But there’s till time on Thursday! Resolve to do better! The Future is Now!

We also talked about the early days of animation, particularly the contributions of one Walter Disney. He’s gotten a bad rap among the teenagers of our time, and for good reason with the company that bears his name churning out turd after well-polished turd. But back in the day, when he and Mickey Mouse were just getting aquainted, he was the best in the business, just as funny and quirky and rascally as anyone out there right now.

If you doubt me, take a look at the old watershed Steamboat Willie. Or Plane Crazy.

We also watched the first Silly Symphonies, The Skeleton Dance and Flowers and Trees.

“You ain’t heard nothin’ yet.”

September 21, 2007

This week we moved on into the sound age, the “talkies” and all the beauties and difficulties thereof. True, none of the “silent” movies were really silent. Every theatre had at least a piano or organ, and the bigger ones featured a live orchestra. But it wasn’t until 1927 that audiences could actually hear the actor’s voice coming from the screen (or speakers behind the screen). At first, studios thought this might be a passing fad. But millions flocked to see Al Jolson in the Jazz Singer and his immortal line, “Wait a minute… wait a minute. You ain’t heard nothin’ yet.” So the rest of the studios joined in and embraced the new technology.

Download the worksheet here: music and sound handout

The answers are as follows:

As we saw in a clip from “Singin’ in the Rain,” this was a tricky transition. Performers had to huddle around microphones hidden in plant pots. Noisy cameras had to be placed behind glass in an immobile soundproofed booth. Crosscutting was all but prohibited by the difficulties of matching sound and vision. Not to mention many of the actors whose voices didn’t match their appearance. “The subtle imagery of the silent era had been replaced by illustrated radio.” (-John Naughton) You probably won’t see many more boring films that those made in 1928-29 (except the few that were still silent, like Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. Check it out, y’all, it’ll blow you away.)

But by 1930 the technical hitches had largely been ironed out and the masterpieces began to flow. If you’re curious, check out Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail, Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front, or Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel.

For the most part, the sound effects in these early movies were pretty straightforward. They used whatever sounds were made on set during production. But in 1933, with King Kong, sound designers started getting more creative. They used their imaginations for what a dinosaur and a giant gorilla might sound like. And not just what they might actually sound like, but what they should sound like, what sounds would add the best effect to their movie. Rather than recording a real gorilla, they used sounds of a lion for King Kong’s voice, and used another lion played backwards for the T-rex. When Kong breaks the dinosaur’s jaw, we don’t hear a real bone breaking, but more like a tree trunk cracking. Thus was born the classicist tradition of sound effects.

See, with classicism, we don’t want the actual sounds, we want heightened impact, we want what it should sound like. We don’t want to hear real punching sounds during a fistfight. You can’t hear real punches, they aren’t loud enough. We don’t want to hear real laser sounds in star wars. Real lasers don’t make any sound. We want the ideal sound for the moment. And we want the sounds recorded in a studio where there’s no airplanes or trucks or babies crying in the background to distract us.

Realists on the other hand are happy to use the sounds of real life. If you’re filming an interview in a backyard, and the neighbor is mowing their lawn, no problem, it adds to the environment. Realists want to show how it actually sounds

Expressionism.

September 14, 2007

“Ask a German moviegoer of the late 1910s to name their favorite movie and the chances are it would have come from either Hollywood or Scandinavia. The dark, brooding dramas directed by Danes such as Carl Dreyer and the Swedes Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller left an indelible mark on the German film psyche. Shadows, symbolism, and the supernatural were the truest expression of the defeated nation’s postwar despair.” -John Naughton, Movies, a Crash Course

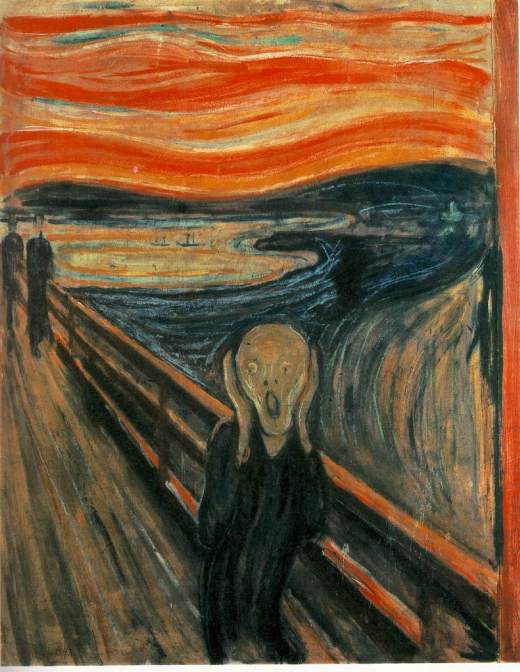

The industrial revolution was in full swing, with one man in a tractor doing the work of fifty farmers. So what did all these ex-farmers do? Well, there were plenty of new jobs in the modern factories. What did these factories do? Assemble pots and pans, automobiles, or maybe ammunition, lots of ammunition. What did they need so much ammunition for? To put in the newly invented machine guns and warplanes and tanks. Yes, technology can make things very convenient, but it has always had a dark side. In just a few years, more people died in World War I than any previous war. So after the war things were looking pretty bleak in Europe. So bleak, that painting pictures of beautiful people doing beautiful things just didn’t seem to cut it anymore. Instead artists like Edward Munch went more in this direction:

Now, if he went out and painted a man standing on a bridge with a lake and hills in the background, and tried to do it as realistically as possible, it wouldn’t look like this. But instead he was trying to paint how this man (or he, the painter) felt, and that requires manipulating reality. That’s what expressionism is all about: an outward expression of inner emotions (that’s the answer to one of the questions!)

Pretty soon this caught on in the film world as well. Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari set the tone. A tale of murder and madness, it used distorted sets, sinsiter backdrops, and stylized acting to convey its narrator’s tnnuos grip on reality. To some it was “painting in motion.” Many later directors incorporated some of these stylistic elements, such at Fritz Lang in Die Nibelungen or Metropolis, G.W. Pabst in The Joyless Street, and F.W. Murnau in Nosferatu and Faust.

Some characteristics of expressionism:

1. Purposefully unrealistic, dreamlike or nightmare quality

2. exaggerated sets, costumes, acting

3. dark/ominous subject and tone

4. Lots of darkness and shadows

5. main character has some kind of unfulfilled spiritual hunger.

6. a search for meaning in an industrial world (often ends in failure).

7. fear of being overwhelmed or taken over by technology

8. Christ figure hero whose sacrifice goes unnoticed.

Depending on which class you’re in we also watched modern clips from Edward Scissorhands, City of the Lost Children, Brazil, and Blade Runner. Can you think of any others that apply?

Download this assignment, and get working!